A Study of Velázquez' Technique Results

In Portrait Pigments for Today

Those perfect flesh tones in the portraits of

Velázquez—available for today's

artists.

(The first of three articles on this subject.)

n

1624, in Madrid, Spain, Diego de Velázquez

stood before his easel. Opposite the great artist

stood Philip IV, King of Spain. As the light

from the window fell on the young monarch's

face, the artist dipped his brush into the white

pigment, then into yellow ochre, and finally

into mercury vermilion, the warm red then in

use. The artist's brush swirled the three pigments

together, producing just exactly the shade on

the king's forehead. n

1624, in Madrid, Spain, Diego de Velázquez

stood before his easel. Opposite the great artist

stood Philip IV, King of Spain. As the light

from the window fell on the young monarch's

face, the artist dipped his brush into the white

pigment, then into yellow ochre, and finally

into mercury vermilion, the warm red then in

use. The artist's brush swirled the three pigments

together, producing just exactly the shade on

the king's forehead.

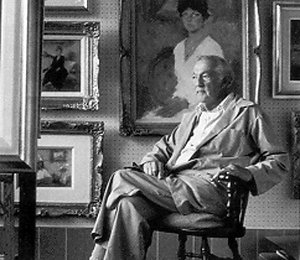

Samuel Edmund Oppenheim

(1901-1992) |

Three hundred years later, in New York, a young

Russian emigré, beginning his art studies,

stood before another Velázquez painting

in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That swirl

of three pigments still lay glistening on the

painted face. Experiments on the student artist's

palette (substituting cadmium red light for

vermilion of mercury) confirmed the mixture.

The young art student was Samuel Edmund Oppenheim

(1901-1992) who became a leading American painter

and teacher. His popular classes in oil portraiture

at the Art Students League of New York (1966-1972)

were innovative and influential. Oppenheim continued

his studies of Velázquez throughout a

long painting career.

Oppenheim's years of intimate and painstaking

scrutiny and analysis of Velázquez paintings

resulted in a series of pigment formulations,

which Oppenheim considered fundamental to the

structure of a Velázquez portrait (for

a detailed description of the pigment combinations,

click on "Descriptions of the Oppenheim/Velázquez

Pigment Combinations" below.) These pigment

formulations were passed on to Oppenheim's students

at the League.

These formulations included three pigment combinations

for light-struck areas (in the normal Caucasian

complexion), two combinations for transitional,

or "halftone" areas, and two darks

for shadow areas. These seven pigments had to

be further modified by the inclusion of additional

colors to precisely match the observed phenomena.

In other words, the Oppenheim/Velázquez

pigment combinations were not "formula"

colors, but simply starting points for the final

color mixture, to be arrived at through traditional

observation-based analysis and adjustment.

In 1974, the Manufacture

of the Velázquez/Oppenheim

Pigment Combinations Is Sponsored by the Art

Students League of New York.

Stewart Klonis, Executive Director,

The Art Students League of New York, who

made possible the manufacture of the Velazquez/

Oppenheim pigment combinations, which became

known as the Pro Mix Color System.

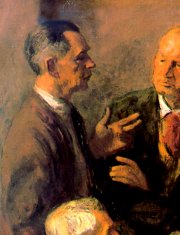

Detail

of the painting Homage to Sargent by Robert

Phillip. Collection, the Art Students

League of New York.

|

|

In 1972, Samuel Oppenheim retired from teaching

at the Art Students League of New York, and

I was hired to teach his class. Eager to perpetuate

his teaching concepts, I formulated the pigment

combinations that he had given us, and asked

the Martin/F. Weber Company of Philadelphia

to produce them. The Weber Company, the oldest

American manufacturer of artists' colors, had

been founded by Frederick Weber, longtime lecturer

on artists' techniques at the Art Students League.

This fact inspired me to approach Stewart Klonis,

Executive Director of the League, with the proposal

that the League serve as financial sponsor for

the colors, which by now had been christened

the "Pro Mix Color System." Mr. Klonis

took the proposal to the League's Board of Control,

which voted unanimously to fund the undertaking.

Thus the Velázquez/Oppenheim pigment

combinations, rechristened the "Pro Mix

Color System" were born, in 1974, with

the League's blessing and financial backing.

The Art Students League,

which, in 1974, provided

financial backing for the

Pro Mix Color System.

In the 32 years since,

50,000 artists worldwide

have used the colors. |

In the 32 years since, the colors have been

purchased by 50,000 artists around the world.

Many of the world's leading professional portrait

artists are devoted to their use.

Over the past three decades, these portrait

pigments have been the object of occasional

criticism by artists not familiar with their

use, the principal charges being that they are

"formula colors" or "shortcuts."

These charges are unwarranted, and I would like

to answer them definitively in the next article

in this space.

John Howard Sanden

The Oppenheim/Velazquez

Pigment Combinations are available as The Pro

Mix Color System from The Portrait Institute at

www.portraitinstitute.com.

Additional relevant material:

Descriptions of the

Oppenheim/Velázquez Pigment Combinations

(Today's Pro Mix Color System).

Returning to the Oppenheim/Velázquez

pigment combinations, it is important to repeat

that these were based on a close scrutiny of

the visible paint film on Velázquez paintings,

both in this country and in Europe. Oppenheim

concluded that there was a basic pigment combination

that recurred constantly throughout the Spanish

master's oeuvre. That combination is best rendered

today by combining white, yellow ochre and cadmium

red light.

Of course, cadmium colors did not enter the

standard list until the nineteenth century.

Velázquez used vermilion of mercury,

a warm intense red, now obsolete. Five of the

Oppenheim/Velázquez combinations are

based on this three-pigment combination: white,

yellow ochre and cadmium red light. Oppenheim

gave us these three pigments in three slightly

different variations, introducing a touch of

cerulean blue into two of them, and numbering

the combinations Light 1, 2 and 3. Light 2 is

slightly darker and more intense than Light

1; Light 3 is darker and more intense still.

Oppenheim returned again to this three-way combination

to produce two transitional, or halftone colors.

Starting again with white, yellow ochre and

cadmium red light, he added a touch of viridian—enough

to produce a soft, delicate greenish halftone

color, especially valuable when painting receding

planes on the Caucasian face. He called this

Halftone 1.

A second halftone color was achieved by reducing

the amount of viridian and introducing a touch

of cadmium orange, producing a warm, rich halftone

color especially useful where light and shadow

areas meet.

For the shadow areas, Oppenheim gave us a powerful,

very proactive pigment combination he had extrapolated

from his study of Velázquez: combining

burnt sienna and viridian produces a rich dark

brown, adding cadmium orange enriches the mixture

still further. This volatile mixture can easily

be moved from warm to cool and vise versa. A

touch of white mixed into this dulls the intensity

slightly and raises the value. Hence the two

"Pro Mix" darks, Dark I and 2.

To quickly reduce the intensity of all colors,

the use of neutral greys—in various values—are

placed on the palette for convenience. Mixing

ivory black with white, and adding a touch of

yellow ochre for warmth, three neutral tones

are created: Neutral 3 (33-1/3%), Neutral 5

(50%) and Neutral 7 (66-2/3%). These grays are

positioned on a value scale of nine tones, with

white being zero, and black, value 9.

Putting the Oppenheim/Velázquez

Pigment Combinations (Today's ProMix Colors)

Into Practice.

The Pro Mix Color System palette consists of

two rows of colors. The top row consists of

twelve standard colors (from left): Ultramarine

Blue, Cerulean Blue, Viridian, Chromium Oxide

Green, Alizarin Crimson, Burnt Umber, Burnt

Sienna, Cadmium Orange, Venetian Red, Cadmium

Red Light, Yellow Ochre and Cadmium Yellow Light.

The lower row consists of (from left): Ivory

Black, Pro Mix Neutral 7, Neutral 5, Neutral

3, Dark 2, Dark I, Halftone 2, Halftone 1, Light

3, Light 2, Light 1 and White. The Pro Mix colors

are adjusted for hue, value and intensity by

mixing with other Pro Mix colors, or with colors

from the upper row of standard colors.

The ten Pro Mix colors are thus not "crutches"

or a "paint-by-number" shortcut. The

ten Pro Mix colors are, in fact, simple traditional

flesh color combinations used by all portrait

artists since the introduction of oil painting.

The artist modifies and adjusts each of the

Pro Mix colors—based on observation of

the subject—in exactly the same way he

would a color from the standard palette. 78

such modifications are demonstrated in the Pro

Mix mixing chart, included with each boxed set

of the colors.

The Traditional Protocol

for All Color Mixtures.

The traditional protocol for all color mixtures

is a four-step procedure. First, the

artist observes the natural phenomena. Second,

looking down to the palette, the artist selects

the single pigment that appears closest to the

desired destination. Third, the artist

must analyze the difference between what is

observed and the color on the knife or brush.

Does the selected pigment need to be adjusted

in hue (made warmer or cooler)? Does it need

to be adjusted in value (made lighter or darker),

or does it need to be adjusted in intensity

or, perhaps, all three of these? The fourth

and final step is to make the necessary

adjustments, by introducing into the mixture

additional, and necessary, components.

|