The Question of the Smile

Why is it that a broad

smile is almost always wrong in a portrait?

n

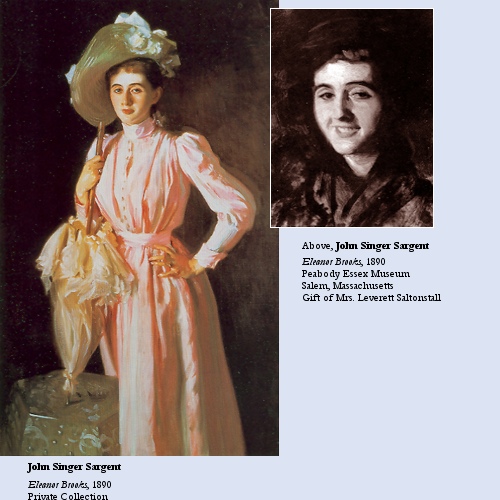

the right above is a sketch by Sargent of Eleanor

Brooks, painted near Boston in 1890, in preparation

for the three-quarter-length portrait shown

here. Obviously, between the sketch and the

final portrait, the artist decided to eliminate

the broad smile. The lady still has a pleasant

expression on her face, but the smile—with teeth showing—has been replaced

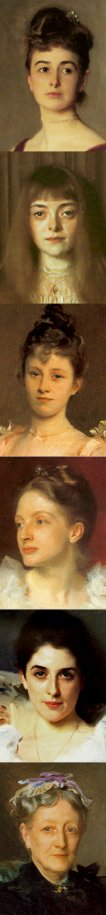

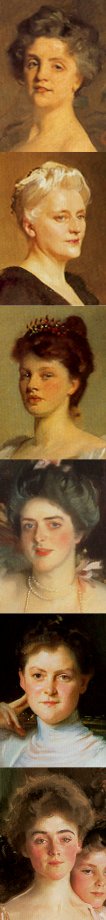

with an attractive, composed expression. Below

are details from twelve other Sargent portraits

of women. Not one is smiling. In fact, a concerted

and deliberate search through Sargent's oeuvre

yields only a handful of portraits in which

the subject has a definite smile on his or her

face. The same is true of traditional, historic

portraiture in general. Why is this? Why does

the working portrait artist consciously feel

his hand and heart restrained when the client

requests a smiling portrait? I think there are

four reasons, all of them potent. n

the right above is a sketch by Sargent of Eleanor

Brooks, painted near Boston in 1890, in preparation

for the three-quarter-length portrait shown

here. Obviously, between the sketch and the

final portrait, the artist decided to eliminate

the broad smile. The lady still has a pleasant

expression on her face, but the smile—with teeth showing—has been replaced

with an attractive, composed expression. Below

are details from twelve other Sargent portraits

of women. Not one is smiling. In fact, a concerted

and deliberate search through Sargent's oeuvre

yields only a handful of portraits in which

the subject has a definite smile on his or her

face. The same is true of traditional, historic

portraiture in general. Why is this? Why does

the working portrait artist consciously feel

his hand and heart restrained when the client

requests a smiling portrait? I think there are

four reasons, all of them potent.

A

selection of

non-smiling ladies

by Sargent...

|

|

The first objection to broad smiles in painted

portraits is simply a practical result of the

fact that the standards in portraiture were firmly

established in a pre-camera era. In fact, the

standards for portraiture were established centuries

before the invention of the camera brought with

it the technical capability for capturing fleeting

expressions. The portrait subject patiently enduring

a two-hour sitting in the seventeenth century

would not have been inclined to attempt to hold

a definite expression of any kind, nor would the

painter have thought of asking him to. By the

time the fast-action shutter was invented in the

middle of the nineteenth century, several centuries

had passed since portrait painting had begun to

dominate the art of picture making. The museums

of the world were already filled with important

examples by great artists. The 150 years that

have passed since the development of action-stopping

photography have not been sufficient to erase

or even alter the conventions of the portrait

art.

The portrait—whether carved or painted—has always been regarded as high art.

At its best and most sublime (by Velazquez or

Rembrandt) portrait painting has been regarded

with an almost reverential admiration. "Gravitas"

has been a staple of the qualities expected

in a fine portrait. Flippancy and lightness

are seldom qualities expected in portraiture.

Hence the tendency for a portrait to be composed,

restrained, and even dignified.

There is however, no mistaking the fact that

in the year 2009 the portrait painter goes about

his ancient craft in a world that is drenched

in photography—and photography in which

the technical possibilities increase with every

passing year. In every home, there are literally

thousands of images of the people who live there.

Boxes bulge with photographs by the hundreds.

Computer hard drives are taxed by the sheer

numbers of the images that are fed onto them.

In a high percentage of these personal images—in fact, probably in the majority of

them—the subjects are smiling. I think

it is fair to say that this is the standard

by which household photos are judged. If the

subject of a picture is broadly smiling, the

picture is declared good. If a smile is missing,

the picture is discarded. A group picture is

considered marred by the member who fails to

oblige with the expected smile.

Thus, the pervasiveness of the smile in personal

and domestic photography adds enormously to

the pressure on the portrait painter to fall

into line with the new demand for an almost

universal joviality.

When the portrait artist is asked to contribute

his product into this environment the tension

of those old seventeenth-century standards weigh

heavily upon him. How to resolve this? The only

thing that one can say is that everyone concerned,

when the issue comes up, must realize the simple

fact that the standards for candid photography

and the standards for historic, traditional

portraiture are different. These are different

art forms, with different standards.

The artist, for his part, must hasten to challenge

the idea that the only alternative to a smiling

expression is a sad one. This, he knows, is

simply not the case at all. Between the smiling

and the morose lies the broad central world

of the "composed" expression. The

thirteen women whose portraits by Sargent appear

here exhibit "composed," non-smiling

expressions. It is an unavoidable fact that

the vast majority of the portraits we refer

to as "great" will be found in this

category.

One final factor that should weigh heavily

in the "smile" or "no smile"

discussion is the potential for the decision

to influence the monetary value of the work

of art in question. Yes, I know that the most

famous painting in all the world is famous for

its smile. But the quality that enlivens the

face of Leonardo's Mona Lisa is a very long

way from a broad smile. It is the faintest of

pleasant expressions. And of course the word

most often applied to it is enigmatic—a word which carries with it the awareness that

the expression on her face is very hard to read.

But the point I want to make is that if Mona

Lisa or Madame X or one of Rembrandt's self-portraits—if any of these featured a broad, toothy

smile, the gavel price at Sotheby's would go

down by—I would venture to predict—many millions of dollars.

So far, I have enumerated only the arguments

against the use of broad smiles in classical

or traditional portraiture. But are there any

arguments in favor? I can think of only one,

which I offer herewith with a degree of reluctance.

The reader thus far may wish to protest, "But

this is not the seventeenth century. It is the

twenty-first, and prolonged sittings are no

longer necessary or desirable." That is

most certainly true. In fact, I would go so

far as to agree that the most highly-prized

quality in portraiture today is naturalness.

Perhaps above all else the contemporary portraitist

in 2009 wants the subject of his portrayal to

appear relaxed, at ease and comfortable. Gone

forever are the rigid, Napoleonic poses of earlier

times. Today's sitter wants to be seen as affable,

urbane and friendly. "Approachable"

is the word that business executives use most

often when describing the qualities they hope

to project through my portrait of them. This

over-arching desire brings with it the awareness

that the pose must be natural, even casual,

and the facial expression should convey warmth

and friendliness.

This final awareness of the expectations of

contemporary people towards their own portraits

must not be allowed, however, to confuse or

void the timeless standards of the centuries.

This calls for diplomacy on the part of the

artist, and sensitivity on the part of subject

and client.

If the artist should find himself caught between

the explicit desire of his client for a smiling

portrait and his personal awareness of the wrongness

of this course, one possible denouement would

be to recommend that the oil portrait be displayed

along with framed (and smiling) photos of the

subject (the portrait on the wall, the photos

on the table below). Thus the painted portrait,

with its classical, composed facial expression,

provides a counterpoint image to the candid

photographic smile. The disparate images reveal

different sides of the subject's personality—in the case of a beautiful woman, different

aspects of her beauty.

|